Beverly Guy-Sheftall and Jo Moore Stewart, Spelman: A Centennial Celebration. Spelman College 1981.

Adam Fairclough, A Class of Their Own: Black Teachers in The Segregated South. Belknap Harvard 2007.

The Black Washingtonians: The Anacostia Museum Illustrated Chronology. Wiley 2005.

George Sullivan, Black Artists in Photography, 1840-1940. Cobble Hill Books 1996.

To Conserve a Legacy is where and when the sense of this project of race and photography really begun to take shape for me. The book on Spelman’s photographs was something I remembered, and it gave me early on with some inkling of what archives of photographs at historically black colleges could provide. But it is only with this new technological piece (internet, blogging, scanning and so forth) that I could begin to imagine the possibilities for somebody like me who can’t begin to get physically to all these archives at black schools for envisioning, thinking, teaching and being inspired.

The story of Spelman might provide the corner stone of the chapter or chapters on black education. It is one of the two only black female colleges and it has such a great photographic archive so little seen by the outside world. The way the book is presented, I can’t tell who actually took these photographs. Was there the combination at Spelman as at Hampton and Tuskegee of photographs by teachers, alumni and hired photographers such as Frances Benjamin Johnston?

I always like to know who took the pictures because it helps a great deal with understanding and interpreting the point-of-view, which is usually being represented somewhere. I notice the early shots of graduates mirror again the aesthetic qualities visible in the Paris Exposition photos and in the Johnston photos. Of course, the early faculty of Spelman was white and I am reading Fairclough to gain a better sense of the lay of the land in terms of the different racial dispositions which lead to the various black colleges, normal schools, Baptist academies etcetera. I still haven’t a sense yet of exactly how many different kinds of black schools there were at any given time. But I think that it is something important to know in telling this story of black photography since the photographs obviously were composed in order to serve those interests. It is good to know that there is an archive which resulted in a regular publication because then one learns by observing the process of selection.

Rereading it I don’t think I had realized the extent to which the role of black women and the education of black women and Spelman has been minimized in the telling of the story of the struggle between DuBois and Washington. Of course, the story of black education is central to the unfolding drama of Jim Crow segregation and the struggle for Civil Rights. And it has always seemed to me that the story of black education and the history of black educational institutions function as an essential mystery within the larger mystery of how it is we are ever going to go about getting our people on the right track educationally.

But the piece of it that has made me so curious as somebody who was raised and educated in the North and in integrated private schools about what happened in the South and most particularly in its classrooms is this: if the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement (or cultural nationalism) was about achieving equality, wiping out the caste of slavery, and getting rid of discrimination, the greatest failure has been this eternal problem of mis-education or the lack of an adequate education which continues to plague our children, and to some degree all of us.

In my experience at Cornell’s Black Studies Program, one of the oldest in the country, I got the sense that this yearning for an education that can liberate us is as much of a problem at the Ivy League Colleges and the State Colleges as it has been in the historically black colleges, because the kids at the Ivy Leagues may be able to achieve in a superficial sense but at the price of knowing next to nothing about the struggles and accomplishments of their forebears, particularly their female forebears who were so crucial to their own survival and success.

Anyhow, it goes around and around in circles but what I am trying to say is that education continues to be a hard nut to crack for us black folks. In the discussions of the fight against segregation, the focus is on the physical conditions but what about consciousness and philosophy? And I don’t mean just vocational versus academic. When we are dealing with rural students from very poor communities in a section of the country in which a high school education is still a luxury for a majority of young Americans, why is the most important thing whether or not there is someone qualified to teach Greek?

I knew black women leaders and intellectuals were trivialized but that the story we tell ourselves about the history of black education marginalizes the role of black women even as we are told again and again that the women were the only ones who were able to advance, is ironic. I wonder where Zora Neale Hurston was when all of this was going on. Why didn’t she have the opportunity to be in those earlier classes at Spelman when she might have attended without having to feel as though she needed to lie about her age.

Also that the story of black women’s education would be marginalized by discussions of women’s education is also something I had thought about because wandering through the libraries at Cornell I got interested in this vocational, industrial focus in early women’s education in the form of Home Economics. There was as well a history of a vocational emphasis at Cornell, which had been co-educational from the outset and geared toward farming and rural occupations apparently from the outset.

(My Aunt Barbara was the apple of everybody’s eye when she graduated from Hunter College at 16 in I guess 1943 and went to college at New York University majoring in Home Economics with a focus on Dietetics. It seems unimaginable to me that this was seen as an advance over becoming a maid. It was just the first chapter in a short and tragic life but that’s the other book).

When I saw the Conserving a Legacy exhibition at the Studio Museum the summer of 1999, what really stood out for me were the photographs—15 by Frances Benjamin Johnston’s from the Hampton Album, 13 of the Hampton Camera Club and other anonymous works sent back by Hampton graduates, 3 by Leonard C. Hyman from Tuskegee, 5 by Cornelius Marion Battey of Tuskegee, 7 by Arthur Bedou of Tuskegee, 2 by William Christenberry of Hampton, 1 portrait of George Washington Carver when he was a young man by Charles S. Livingston, 11 by Leigh Richmond Miner at Hampton, 3 by Prentice P. Polk of Tuskegee, 5 by C.D. Robinson of Tuskegee, 1 by Richard Riley, 1 by Herbert Pinney Tresslar, 1 by Doris Ullman and 8 portraits of famous people by Carl Van Vechten in the 30s. Which totals about 69 or 70 photographs.

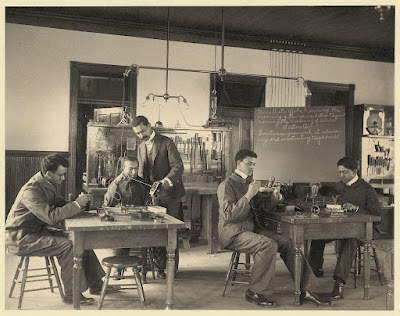

Primarily what interested me in this group were the photos from Hampton and Tuskegee and the different generic conventions they represented. On one level, they seemed somehow highly familiar and yet I also knew even if I had ever seen such pictures before, I knew little about them and the people in them.

At the same time, my preoccupation with African American visual culture in recent years made me immediately aware that here might be some aspect of the archive documenting our steps as a people from slavery to our present marginal status in modernity. It was clear enough that these pictures presented in a fairly straightforward and humble way students and teachers at or around the turn-of-the-century engrossed in the endeavor of educating the former slaves and their children.

I also knew from the central role played by images produced at Hampton and Tuskegee at the turn-of-the-century, as well as images of Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver, that the debate over manual training versus elite liberal arts training had been an issue and that these images portrayed institutions which were ostensibly devoted to so-called “vocational” training. Although I was also aware, given my interest in the Jim Crow violence which characterized this period in the South, that these schools functioned in the middle of an often terroristically violent environment. To look at these often tiny pristine images of African Americans whom I had wondered about so intensely for so long dressed so neatly in their period costumes, so serious in their preoccupation of getting an education and passing it on to the less fortunate children of the rural south was as healing as anything I had ever experienced during my years as a Northern African American. Of course, on some level I had always known there had to be such images since my great grandfathers and great grandmothers were such people, teachers in fact who started small schools in the South. But to actually see them finally on the wall of a museum I admire (not my ancestors particularly but some people like them) was to know immediately that I was going to spend a lot of time finding out exactly where they came from, how many there were and what they signified.

These images gave the lie finally to all the stereotypes that had ever worried me or any other African American. The debate was not even over whether or not they were positive or negative images or role models. It wasn’t a questions of whether the subjects were playing into some preconceived notions of African American abilities or not, as one would be led to believe in a novel such as Invisible Man. The point was that these people were every bit as real as Buck and Bubbles, as Williams and Walker, as Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. And although the talented tenth must have been closer to a one thousandth at the time, nonetheless, they provide the balance of a picture of a people living under apartheid and making the very best of it under the circumstances.

There are the following articles in To Conserve a Legacy concerned with the photographs, short but providing crucial clues to my work:

1. Lux, Lies, and Compromise: The Politics of Light Exposure by Leslie Paisley.

2. Preserving the Cyanotype: Unlimited Access and Exhibition through Digital Image

3. Surrogates by MK Lalor, James Martin, Nicholas J. Zammuto

4. The Hampton Camera Club by Mary Lou Hultgren

5. Chronicling Tuskegee in Photographs: A Simple Version by Cynthia Beavers Wilson